Sally and the Brownie-Hawkeye

- valmpulido

- Oct 30, 2023

- 17 min read

Updated: May 28, 2025

Introduction

One may find layers of entangled identities when looking at relationships between individuals and consumer products. In an approach inspired by material culture scholar, Daniel Miller, this paper will look at the relationship between a young woman in the 1950s and her camera (Miller 2009). As the narrative progresses, separation between the person from the object, the object from the manufacture, and the manufacture from the institution becomes blurred. The relationships in this study are bound within the framework of kinships and social constructs. I ultimately found that the connections between an individual and her camera were also tied to larger social conditions and family ties.

For this study, I looked at relationship features between my mother, Sally Kimble (maiden name Manuela Lozano), and her Brownie-Hawkeye camera. Informational phone interviews were conducted where we discussed her experience with the camera. The narrative below is a hybrid approach that incorporates the interview with supplemental information that provides cultural context. By providing context, we can see how corporate institutional philosophies make their way to identified consumer demographics and influence product experience. This study found that these relationships do not happen in a vacuum but through larger cultural connections. For example, cycles of life, or transformation, is something of a reoccurring theme in this essay; Family dynamics, technology, and commerce experience various forms of birth, death, and rebirth.

December 25, 1952

Lansing, MI

On this day, a thirteen year old Manuela Lozano receives a Christmas gift from her older brother, Carlos. As soon as she opens the package she knows what it is, for the distinct yellow and red box could only mean one thing, a Kodak camera. To be specific, it is a Brownie-Hawkeye complete with a flash outfit. The set comes with a camera, detachable flash mount, Kodak 620 film, flash bulbs, and a user’s guide. Carlos, is a young man in his early twenties and has a good job at Motor Wheel a few miles away. Motor Wheel is best known for having made, though not exclusively, automotive tires. Their father, Armando, works there too. He has been employed there since 1948 when the Lozano family moved to Lansing from Laredo, a city in Texas that sits just north of the Rio Grande. Manuela’s family use to call her Manny for short, which means With God, and she did not speak English by the time she arrived in Lansing. There, she attended Catholic school where the nuns changed her name to Sally because it sounded less ethnic. Within the next eight years, she too will be a Motor Wheel employee. Somewhere, there exists a photo of her at work on the line wearing a bandanna looking like Rosie the Rivetter.

The story of Sally and her Brownie-Hawkeye is far more complicated than meets the eye. In a sense, this is a quintessential American tale. No single actor, including the camera, got to where it was by accident that joyous Christmas day. If one was to zoom out the metaphorical lens, that person would see various forms of movement spurned by economic activity and technological innovation that is synonymous with the conditions that was ubiquitous in America’s consumer culture during the Fifties. In 1945, sociologists Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore articulated the functional theory of social stratification where individuals are identified in systems of position in degrees of status (Ritzer 1992). In this light, members within the same strata are orientated towards like symbolic systems and cultural values (Ritzer 1992). But, in the 1950s things get a little ambiguous as a more diverse range of ethnicities experience upward social mobility as identified in a study by marketing scholar Pierre Martineau who notes, “there are no hard fast lines between the classes (Martineau 2

1958).” He goes on to state that psychological awareness of one’s class position dictates consumption decisions, but as the perceived differences of what defines the social strata eroded, the consumption decisions of the working class and semi-skilled broadened into market segments that were previously restricted (Martineau 1958). The Lozanos were a part of this nationally recognized upward shift, and were one of many Mexican-American families who migrated to the Lansing area for work in the growing automotive industry. This mass migration has given the capitol city a large Hispanic population, particularly on the north side.

The mid-twentieth century is warmly remembered as a time of prosperity for longtime Lansing residents. It was the sort of prosperity where a young Latino man could easily purchase consumer goods. Perhaps he was further enticed after seeing one for sale in a local drug store advertisement calling out; Wanted! 10,000 Beginners to Take Indoor Flash Pictures-With Easy-to-Use Eastman Flash Cameras (Muir’s 1952). Entry level Kodak cameras, including the Brownie-Hawkeye, were a regular feature in newspaper advertisements for nearby camera shops, department stores, and drugstores, such as Muir’s Cut Rates Drugs located on 229 South Washington Street, not two miles away from the Lozano home. Another advertisement for the Lansing Camera Shop features the Brownie line as “Inexpensive: Simple yet Capable”, and refers to the Brownie-Hawkeye as “a smart little box camera with 1951 styling (Lansing Camera Shop 1951).” Inexpensive and easy to use, a good gift for a precocious child.

Kodak & Amateur Photography

The Eastman Kodak Company was a ubiquitous marketing entity throughout the twentieth-century. “All I knew was Kodak when I was a kid. Them and Argus. But Kodak commercials were on T.V. all the time,” Sally said. Even the word, Kodak, is a fiction rooted in lore. The story goes, George Eastman was intrigued in the letter K and thought it powerful, yet catchy, and the repetitious Koh sound would prove infectious (West 2000). Kodakery (magazine), Kodachrome, Kodacolor, and phrases like “It’s a Kodak moment” and “Let your children Kodak” were phonetic cues linked to the expectation of quality (West 2000). Kodak became a household name through relentless advertising campaigns spanning decades.

In curating its image, Eastman-Kodak invested into public outreach encouraging people to participate in amateur photography. During the late 1800’s, Kodak was sponsoring amateur photography contests, which in 1900, extended competition to children with the advent of the Kodak Brownie (Dowling 2015, West 2000). Excitement was generated with the prospect of creating professional level photographic quality that could be achieved through mere snapshots (Dowling 2015). The implementation of amateur photography was an important component in Kodak’s marketing, for it was featured in the pages of Kodakery, a magazine dedicated to amateur photography in the early twentieth-century, and print advertising (Oliver 2007). Kodak also made initiatives to spurn camera clubs in its earliest days and it was a concept that stuck for many people. A 1953 Lansing State Journal article recommends joining a camera club to improve skill, socializing with other photographers, and go on field trips (Desfor 1953).

Affordability was another important component for Kodak’s engagement with amateur photography. According to West, the advent of the Kodak Brownie in 1900 ushered in a whole new demographic into the photography market by setting the price at one dollar, which before then, the cost of the most modest cameras were still beyond that of the average consumer (West 2000). Also, the design of cameras were restrictive for practicality reasons because the bulky equipment was too heavy to carry around (Bennett 2004). The Kodak Brownie was infinitely lighter than its predecessors being made of jute board covered with imitation leather and equipped with an inexpensive lens while being mechanically uncomplicated (West 2000). Kodak expressed a commitment to ease of use as evident with the slogan, “you push the button, we do the rest,” meaning the camera (with film) could be sent to the Kodak factory in Rochester, New York for development and returned to the user with printed photos (Bennett 2004). Film development was a process that was previously unavailable for most anybody at that time; Anybody can now be a photographer, which was the ethos to Kodaks success.

The Camera Design

The look and feel of the Brownie-Hawkeye is the collective brainchild of four men; Leo Baekeland, Walter Teague, Douglas Harvey, and Arthur Carpsey. The evolution of the original 1900 Kodak Brownie box camera was incremental until the mid 1930s when the Baby Brownie was introduced. As the name indicates, the Brownie-Hawkeye is a merger of two lines of Kodak cameras; the Brownie and the Hawk-Eye. Unlike the Hawk-Eyes, the Brownie line was not exclusively box-type cameras, but it was considered Kodak’s economy line, which also included movie cameras. During the 1930s, the Hawk-Eyes and Brownies alike offered models of box-cameras that featured art deco motifs. One particular model, the Baby Brownie (a box camera of small size), was particularly influential on the Brownie-Hawkeye for two reasons; One, it was the first Brownie camera made from Bakelite resin, and two, it was designed by renowned industrial designer Walter Teague, who’s art deco flare was impressionable on designer Arthur Carpsey (Carpsey 1948). Bakelite resin, invented by chemist Leo Baekeland, had been used in consumer products for decades by 1949 when the Brownie-Hawkeye first appeared on store shelves. But, the compact durability of the material in conjunction with its opaque quality made it ideal for cameras into the early 1960s (professionalplastics, vintagecameralab.com).

Aside from durability, function is important to the development of the Brownie-Hawkeye. While conducting research, I noticed a significant gap of product development involving Kodak box-type cameras between the Baby Brownie of 1934 and the Brownie-Hawkeye in 1949. Having searched local advertisements for camera products from the late 1940s to the early 1950s, the Brownie-Hawkeye was the only of its kind to not have been developed in the 1930s. It is conceivable that the events surrounding World War Two could have impacted product innovation. In any case, by 1946, Douglas Harvey patented improved shutters for economic lenses and a single-latching mechanism exclusively for the Brownie-Hawkeye (Harvey 1946). Additionally, the Bakelite technology allowed for flushed buttons and switches that were not possible on earlier cardboard and metal cameras, giving the Brownie-Hawkeye its iconic streamline art deco appearance (Art Deco Cameras, 2020).

The Family Photographer

Carlos, was the sort of person who always had the latest gizmos and technology. He endlessly showed family pictures whenever guests came over to visit. Throughout his life, Carlos always had all the latest in audio and visual technology; slides, filmstrips, and eventually VHS tapes. That Christmas of 1952, Sally wanted a Brownie-Hawkeye because she liked her brother’s old Kodak box camera and wanted one of her own. “I loved it, it was my pride and joy,” she recalls fondly “I used it a lot. I took it everywhere I went, I became the family photographer.” This real life scenario is reflective of a page straight out of the Kodak marketing playbook. In the book, Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia, Nancy West describes the strategy laid out by Kodak executives in 1912 where Brownies were aggressively marketed to children as an introductory vehicle to photography so they may quickly grow out of it and want to try more advanced and more expensive camera models; Thus, enabling the child to hand down the Brownie to a younger sibling (West 2000) . Here, the box camera owned by Carlos had inspired him to explore other technologically advanced forms of photography and media, which in turn, heavily influenced his younger sister.

When asked if there it was an interesting experience in taking a shot with the Brownie-Hawkeye and she said, “no, nothing like that, there was nothing to it. You just point and click.” She goes on to say, “I used it for family gatherings; for holidays and celebrations. When my nephews, the twins were baptized. Birthdays. School friends.” When asked to elaborate on that she said, “I took pictures of the class officers, like the president and treasurer. This was when I was in high school at St. Mary’s.” I asked Sally if she would make trips to out and shoot where she replied, “I use to like to go to Potter’s Park and shoot there. They use to have these floral arrangements. I would shoot them with color film, but the images came out kind of faded. They did have much contrast. But they were good quality.”

Sally recalls a time when she brought her Brownie-Hawkeye on a family vacation from Lansing to Laredo. “My dad would just drive through, we didn’t really stop,” she said replying when I asked her about stops along the way, but then she said, “we did stop at a motel for the night after we passed San Antonio and that was our first time ever staying in a motel.” Sally goes on to say, “the next day I asked my dad if we can turn around and go back to see the Alamo. I was his little girl and he couldn’t say no to me, so we did and we all had a really good time. Even my mom, she didn’t want to go at first. But we went sightseeing, I got pictures of the River Walk and the Alamo.” Talking about the Alamo, she says, “at the time it was just a shell, there was nothing inside. I was hoping there would be a gift shop or something.” When asked what made her feel so compelled to see the Alamo, she said, “The Disney shows, Davy Crockett and the Alamo. I didn’t even know of it until I learned about it on TV.” She mentions, “afterwards we went out for a nice dinner there. My dad really like to dine and eat well. I remember we ate at this restaurant that had wrought iron balconies you can eat on.”

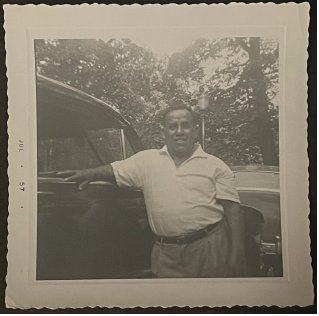

Of the few remaining photos from her Brownie-Hawkeye, the picture of her father taken when she was eighteen years of age, is one of her most beloved. Sally absolutely adored her dad. In the photo he is leaning against his car, which is fitting because, as she puts it, “he was such a car guy. He loved his cars and he loved to drive.” Cars were a part of Armando’s identity. His obituary reflects his admiration for automobiles that existed even in his place of employment…

LOZANO, ARMANDO M., 79 of 2513 W. Dunlap,

a Motor Wheel retiree, died Friday.

(LSJ 1979)

One of Sally’s favorite memories with her camera was when she took a great shot of Bill Haley preforming in concert. “I just went up and took the picture, nobody was in their seats, we were all dancing and enjoying the show. Bill Haley was the biggest star until Elvis came along. I got a few other shots but I don’t know where they went. Your sister probably has them.” The Biggest in Person Show of ’56 was a touring live music event that was a big deal because it featured a number of musicians in Rock n’ Roll and Rhythm and Blues preforming their hit songs. Upon hearing the show would be coming to the Lansing Civic Center, Sally asked her brother if he would be interested in going with her to see the concert. After saying he would, she made a trip down town to the Civic Center box office where she got two tickets for three dollars each. For the occasion, she also got him a new shirt, slacks, and wing-tipped shoes so he would look cool for the event. Sally recalls the ticket price being a little steep, which makes sense given how close she got to Bill Haley when she took his picture. “I was in high school and I had a job, I didn’t care about the money,” she told me. Two weeks leading to the show, a Lansing State Journal article read “Bill Haley’s Teen Show Due Nov.1” and highlighted some of performers such as The Platters (Only You), Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers (Why do Fools Fall in Love), and Chuck Berry (Roll Over Beethoven) and others (Uncredited 1956).

“I remember it ending early and Charlie had to work the next day,” Sally said. There were two shows that Thursday night; one at 7pm and the other at 9:30pm. At some point shortly after the show, Sally got separated from her brother and made her way onto a tour bus where she met some of The Teenagers. Being that they attended the early show, the talent was still waiting around until it was their time to go back on stage. “They were all kids my age, they were very approachable.” The Teenagers told her she could meet Frankie, who was fourteen at the time, was sitting just a few rows back. She declined because he looked relaxed and didn’t want to bother him with her star stuck-ness, Sally said, “There wasn’t any security back then, I just walked onto the bus.” After she got off the bus, she was about to resume looking for her brother when Chuck Berry called her over from his convertible car. He asked, “How do you say I love you in Spanish?” Chuck Berry and Sally were still talking when Carlos found her and said its time to go, much to her chagrin.

Her Brownie-Hawkeye was present at another milestone moment in her life. “The camera was with me when I went on my first date with your dad. I don’t remember who, but someone took a really nice picture of us with that camera and it came out really good,” then Sally goes on to say, “it was in Jack and Peg’s garage. That would have been July of 1957, it was my friend Kay’s birthday party. There was a table with a record player. We listened to music and danced right there in the garage.”

Camera Shops

When asked about getting the film developed she perked up, “Oh that was my favorite part.” Sally worked for a camera shop called Van’s Photo Service in Lansing from 1955-1960. As I looked for advertisements they may have released, I noticed several where their logo was a scotty dog taking a picture. “Yeah, that was his dog, Mr. Bassler, I never did know his first name but he was very debonair. He loved his dog and he loved cats. He once fired someone for pushing a stray cat off a picnic-table while taking a break outside.” Getting back to film she said, “I could developed my own film, I ran the processor. There was the processing tank that had all the chemicals. It went develop, stop, rinse and then it went on a hot drum to dry. Then they would go to the printing area where we used what was called deckled edges, that’s like when its frayed on the sides. And then we would cut them. I forgot what the size was, three by three I think. There was a number system that was on the film roll that was used on the envelope for the pictures. Sometimes they would get mixed up, but that happens” she said with a laugh.

Though not completely extinct, the camera shop is something of a rarity these days. The Lansing area had several to choose from by the mid 1950s. In 1955, Van’s Photo Service opened their second store, while that same year, Linn Camera Shop would open their third store in the new Frandor Center (Van’s Camera Shop 1955, Uncredited 1955). A Lansing State Journal article noted that in 1914, the Linn Camera Shop was the first in town to render photofinishing service through drugstores (Uncredited 1955), a practice that further gave rise to the amateur photographer. The promotional spread for a 1953 edition of the State Journal emphasizes the connection between pop-culture and photography with a full page advertisement for the Vincent Price 3-D classic, House of Wax. In celebration of the film’s release, the mayor of Lansing declared the period of May 15-21 as “3D Week” for the city (Warner Brothers 1953). Under the announcement for the film and 3D week are three separate advertisements from competing camera shops (Griffith’s Photo Supply, Van’s Photo Service, and the Lansing Camera Shop), all of which are promoting the Stereo-REALIST camera that can take pictures in 3D and could also be projected onto a screen (Warner Brothers 1953). Sally recalls seeing the movie, “I saw it at the Michigan Theater by myself after school. I was really anxious to find out what “3D” was. It was really entertaining to be part of the movie. When an object would fall, it seemed like you had to duck or get hit.”

New Camera

Sally remembers taking the Brownie-Hawkeye on a family vacation, only this time, it was a family of her own. “I had it (the camera) when we went to Canada, when we took the kids to Niagara Falls.” The kids she is referring to are my four oldest siblings. “Ginger was just a toddler and Dodie couldn’t even walk yet, so this must have been in 1965. We drove from Lansing, to Detroit, to New York, and then to the Falls. We camped when we stopped overnight because it was cheaper than staying a motels all the time. But I got shots of the Statue of Liberty. They wouldn’t let us go up to the torch, it was being repaired or something, but we went up to the crown. I remember your dad carrying the two girls up the whole way, he never put them down.” I asked her how long was the trip, she said, “it was a couple of weeks. I didn’t work because I was with the kids. Your dad was doing some kind of metal work, fabricating.” Sally went on to say, “I stopped using the camera a little after that. It must have been about that time. I got a new Polaroid. I liked the instant film.”

Conclusion

There is a saying in advertising that goes, “You don’t sell the steak, you sell the sizzle.” Kodak was no exception, their steak was inexpensive cameras and their sizzle was easy nostalgia. A large component of Kodak’s business model was not so much based on camera sales, but rather film and chemical processing (Lucas 2009), which explains why Kodak could sell cameras cheap or even give them away. Kodak, as an American institution, has fallen from great heights since the 1990s with the advent of digital imaging technology. Many articles have been written how the company fell victim to Christensen’s theory of disruptive technologies that states, investing in disruptive technologies is not a rational financial decision because disruptive technologies are initially of interest to the least profitable customers in a market (Lucas 2009). Another perspective that could be amended to Kodak’s downfall was underestimating sharing images would be conducted through virtual platforms as oppose to physical mediums (Anthony 2016).

The scenario above is not to demonstrate the management practices of corporate entities but to invite a larger discussion of cultural loss, particularly where process is involved. In 1888, professional photographers were openly criticizing the Eastman-Kodak for cheapening their profession by making photography out of snapshots (Bennet 2004, West 2000) in similar fashion to Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram, which featured image filters that gives the allusion of film through digital technology while being instantly sharable through social media platforms (Anthony 2016). The fall of Kodak emphasizes two points of loss. The first is the institution of Kodak bringing devices of art and science to the masses, which further invites a dialectic of perspectives. On one hand there is the critique that suggests the commercializing of modern and magic as a form of visual communication was little more than a superficial ploy to reach a new consumer base (Oliver 2007). On the other hand, there is the loss of particular crafts, as Walter Teague himself expressed in a 1957 lecture where he is essentially discussing adapting disruptive techniques, “My (design) tools then were factories…of power and precision,” but he notes that change in technique and process is essential, “…proper and beautiful work called for a wholly different set of skills from those the old-time craftsmen” (Teague 1957). As for the Brownie-Hawkeye, the simplicity is a marketing ploy while the complexity resides in the object’s design, the photographer’s vision, and the marketing strategy itself.

While it could be argued that the Brownie-Hawkeye was never really about craft, a number of modern day film camera enthusiasts may not totally agree. When Sally commented earlier that the camera had a faded color look, she was talking about soft tonal quality that comes primarily from low quality lens and its outer protective plastic covering (photojottings.com). This is a characteristic many of today’s photographers still appreciate and utilize in their work by incorporating the Brownie-Hawkeye and other comparable vintage cameras. Film cameras are experiencing renewed interest from people who have owned, or never owned, one when they were younger. Due to the functional durability and ease of use, the many Kodak Brownie-Hawkeyes are objects of nostalgia capable of producing nostalgic content that is finding social relevancy today.

Bibliography

Anthony, S. (2016, July 15). Kodak’s Downfall Wasn’t About Technology. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/07/kodaks-downfall-wasnt-about-technology

Art Deco Cameras.(2020) Retrieved from http://www.artdecocameras.com/resources/bakelite/

Bennett, R. (2004). OUR LIVES IN SNAPSHOTS. The Saturday Evening Post (1839), 276(4), 14.

Carpsey, A.H. (1948). Design for a Box Camera (U.S. Patent No. 151965). U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/9d/67/8e/5b45b577fd0ce1/USD151965.pdf

Cohen, Lizabeth. 2004. A consumers’ republic: The politics of mass consumption in postwar America. Journal of Consumer Research 31(1): 236-239.

Desfor, I., (1953). Joining Club Helps Solve Problems. Lansing State Journal), 58.

Dowling, S. (2015, January 5). The most important cardboard box ever?. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-30530268

Eastman-Kodak. (1950) Brownie Hawkeye Camera: Flash Model. https://www.brownie-camera.com/manuals/bhawkeyeflashmod.pdf

Garnett, J. (2020, October 1). Adding to the Zoo During the Great Depression. potterparkzoo.com. https://potterparkzoo.org/tbt_9/

Harvey, D.C. (1946). Blade and Cover Blind Shutter for Cameras (U.S. Patent No. 2,472,587). U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. http://www.camarassinfronteras.com/kodak_duaflex_IV/patentes/1949_06_07_US2472587A_shutter_mit_flash.pdf

Harvey, D.C. (1948). Camera Part Latching and Guiding Construction (U.S. Patent No. 2,548,529). U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. https://www.freepatentsonline.com/2548529.pdf

Higgs, K. (2021, January 11). A Brief History of Consumer Culture. The MIT Press Reader. https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/a-brief-history-of-consumer-culture/

Kimble, M. (2021, November). Personal communication [Interview].

Lansing Camera Shop (1951, July 29). Kodak and Brownie [Advertisement]. Lansing State Journal, 38.

Lucas, & Goh, J. M. (2009). Disruptive technology: How Kodak missed the digital photography revolution. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 18(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2009.01.002

Martineau. (1958). Social Classes and Spending Behavior. Journal of Marketing, 23(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.2307/1247828

Miller. (2009). Anthropology and the individual a material culture perspective. Berg.

Muir’s (1952, November 13). Wanted! 10,000 Beginner [Advertisement]. Lansing State Journal, 26.10

Niederman, R. Antique Wood Cameras. (2000). Retrieved from http://www.antiquewoodcameras.com/hawkeye.html

Oliver, Marc. “George Eastman’s Modern Stone-Age Family: Snapshot Photography and the Brownie.” Technology and culture 48, no. 1 (2007): 1–19.

Professional Plastics. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.professionalplastics.com/BAKELITE

Ritzer, G. (1992). Contemporary Sociological Theory. McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Uncredited. (1956). Bill Haley’s Teen Show Due Nov. 1. Lansing State Journal, 18.

Uncredited. (1955). Third Linn Camera Shop Ready to Open in Frandor. Lansing State Journal, 12

Van’s Camera Shop (1951, July 29). Kodak and Brownie [Advertisement]. Lansing State Journal, 38.

Warner Brothers (1955, October 16). Grand Opening [Advertisement]. Lansing State Journal, 27.

West, Nancy Martha. Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Comments